The University of Toronto Archives is pleased to announce our recent acquisition of over 400 nineteenth century stereographs, which were collected by Sir Daniel Wilson, U of T’s president from 1880-1892. Harold Averill, Assistant University Archivist, explains the context of the collection below.

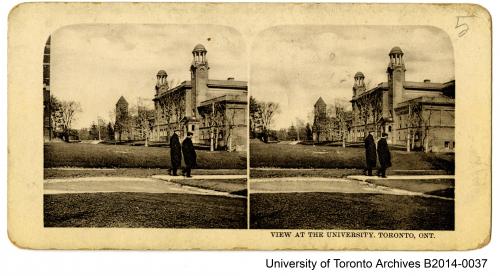

Included in the collection are the 3 stereographs shown here:

- An early, and rare, view of the University Museum at University College, which was destroyed by fire in 1890.

- A view of the University of Toronto medical building at the University of Toronto.

- A view of Wilson’s home country: Scotland’s Pride – The Great Forth Bridge and the Highland Kilt.

Sir Daniel Wilson, who ended his life as President of the University of Toronto, was much more than his title suggested. Early on, his interest in archaeology and in art (he studied under J.M.W. Turner) established him as an authority on ancient Scottish history. After he came to the University of Toronto as chair of English literature and history, he introduced the first courses in ethnology in the British Empire and collected skulls. In his paintings, he created a visual record of his travels and interests.

When Robert Stacey mounted his exhibition, “Sir Daniel Wilson (1816-1892) : Ambidextrous polymath”, in the University of Toronto Art Centre in 2001, he illuminated further the life of this remarkable transplanted Scot who had recently been rescued from comparative obscurity in Elizabeth Hulse’s edited volume (1999), Thinking with both hands: Sir Daniel Wilson in the Old World and the New.

Both the catalogue and the book drew on scattered resources in archives, art galleries, and museums, but neither provided much information about one of Wilson’s interests – photography – which had recently been unearthed by Les Jones in a shop in Toronto. What Mr. Jones had found was a collection of over 400 stereographs that, from the handwriting and other evidence, he deduced to have been assembled by Professor Wilson and members of his family.

This collection, now in the possession of the University of Toronto Archives, is a delightful visual record of Wilson’s interests and the work of some of the photographers of his day. There is no surviving evidence that he himself took photographs, but he regularly requested them from his friends and purchased others from commercial suppliers during his travels.

The collection dates from about 1855 to 1908 and is divided into three broad categories: Europe (Scotland, England, France, and Italy), the United States, and Canada, though there are a few images from other places, including Tasmania. His antiquarian interests are reflected in the photographs of old Edinburgh, Chester in England, and in some of the earliest photographs snapped in the Hebrides. He was also interested in the historical building, monuments, and streetscapes of cities such Paris, Rome, New York, Washington, Montreal, Ottawa, and Toronto (including the University of Toronto and the Toronto Magnetic and Meteorological Observatory). He visited Washington in 1863 and walked out over nearby Civil War battlefields, of which two stereographs have survived. When he travelled through smaller centres he collected as he went; thus, there is a stereograph of the sawmill in Hawkesbury, Canada West.

Wilson was also interested in the physical landscapes of North America and collected stereographs of such places as the Yosemite Valley in California, the rugged canyons of Colorado, Niagara Falls (mostly of the American side), and Lake Superior along which he had first canoed in the 1850s. The numerous depictions of the White Mountains in New Hampshire were scenes familiar to him from his vacationing there in the 1880s, and which he painted for relaxation. Interestingly, there are also images of the Klondike, from 1898 and 1899, which may have been sent to his daughter by George Mercer Dawson, the family friend, scientist and surveyor after whom Dawson City is named.